URLs, HTTP and servers

During this whole guide so far, you’ve been using Mastro as a static site generator: when you hit the “Generate” button, it creates the html files, which GitHub Pages exposes to the web somehow. But how? What actually happens when you hit enter in your web browser after typing in some URL like https://mastrojs.github.io/guide/?

Broadly speaking, your browser makes a request to a server, and that server sends back the HTML. A server is ultimately a computer that usually sits in a data center, and is running a program that answers these requests. Confusingly, that program is also called a server.

Anatomy of a URL

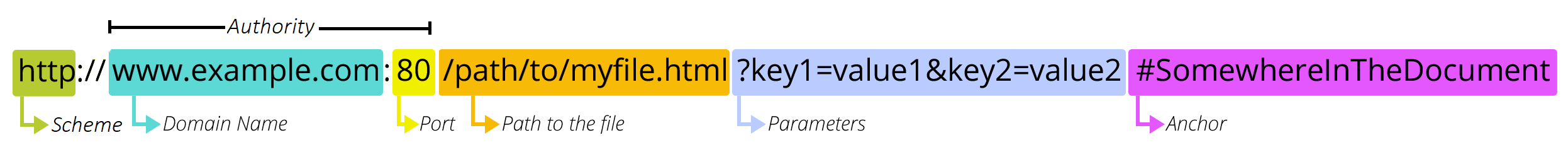

Let’s take a closer look at the above URL. It consists of three parts:

https(known as the scheme) tells us that we will use the HTTP protocol to talk to the server (actually HTTPS – HTTP but securely encrypted).mastrojs.github.iois the host part of the URL: it identifies which server on the internet to send the request to. It consists of three parts in turn:.iois the top-level domain (the most famous TLD is.com)github.iois known as the domainmastrojsis the subdomain (the most common subdomain iswww)

/guide/is the path – it tells the server which page we’d like to see.

Actually, there can be a few more things in a URL:

We’ll get to the port and the parameters later. The anchor is the only part of the URL that’s not sent to the server, it merely allows the browser to scroll directly to the element with the id specified in the anchor (sometimes also known as a hash). You can see it in action when clicking a link in the table of contents of a larger Wikipedia article, for example.

An HTTP request and response

Now, to actually send a message over the internet to that specific server, the browser needs to know the server’s IP address, which is a long number that’s hard for humans to remember. To find it, the browser does a lookup in the so-called Domain Name System (DNS). If you want your website to be availlable under a custom domain (instead of a subdomain of github.io), you need to pay a registrar, like Hover, to register it in the Domain Name System. (I wouldn’t recomend GoDaddy, which features some dark UI patterns.)

The HTTP request that your browser (aka the client) sends to the server when you hit enter might look something like this:

GET /guide/ HTTP/1.1

Host: mastrojs.github.io

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Mac OS X 10.15) Firefox/139.0

Accept: text/html

Accept-Language: en-GB

It’s a HTTP GET request for the /guide/ page, using version 1.1 of the HTTP protocol. The Host HTTP header field mentions the server’s hostname, the User-Agent header identifies the browser making the request: in this case Mozilla Firefox on Mac OS X. The last two headers let the server know that we’d like the response to be HTML, and preferably in English as spoken in Great Britain.

If all goes well, the server answers with an HTTP response. It starts with the response headers, followed by an empty empty line, followed by the response body containing the HTML. Thus it might start as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

content-type: text/html

last-modified: Mon, 23 Jun 2025 13:07:45 GMT

content-length: 6172

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

Notice the 200 OK on the first line? 200 is the HTTP response status code for “OK” – meaning the server understood the request and managed to send a response. Apart from success, status codes fall into three classes:

3xx(like301or303) are redirects.4xxmeans something went wrong and the server thinks it’s the client’s fault. The most common one is404 Not Found, which means the server does not have the page which the client requested.5xxmeans the server ran into some kind of problem when trying to answer. Perhaps it was overloaded or crashed due to a programming error.

As you can see, loading an actual website over the internet is way more complex than opening a static HTML file stored on your laptop’s harddisk. It’s a dynamic process, involving a sort of negotiation between the client (usually the browser) and the server, and can lead to different results depending on the systems currently online and how they’re configured.