Introducing JavaScript

Now that you got a taste of HTML and CSS, let’s talk about JavaScript. It’s the third language that the browser understands. One of the easiest ways to get your feet wet with JavaScript, is in your browser’s console.

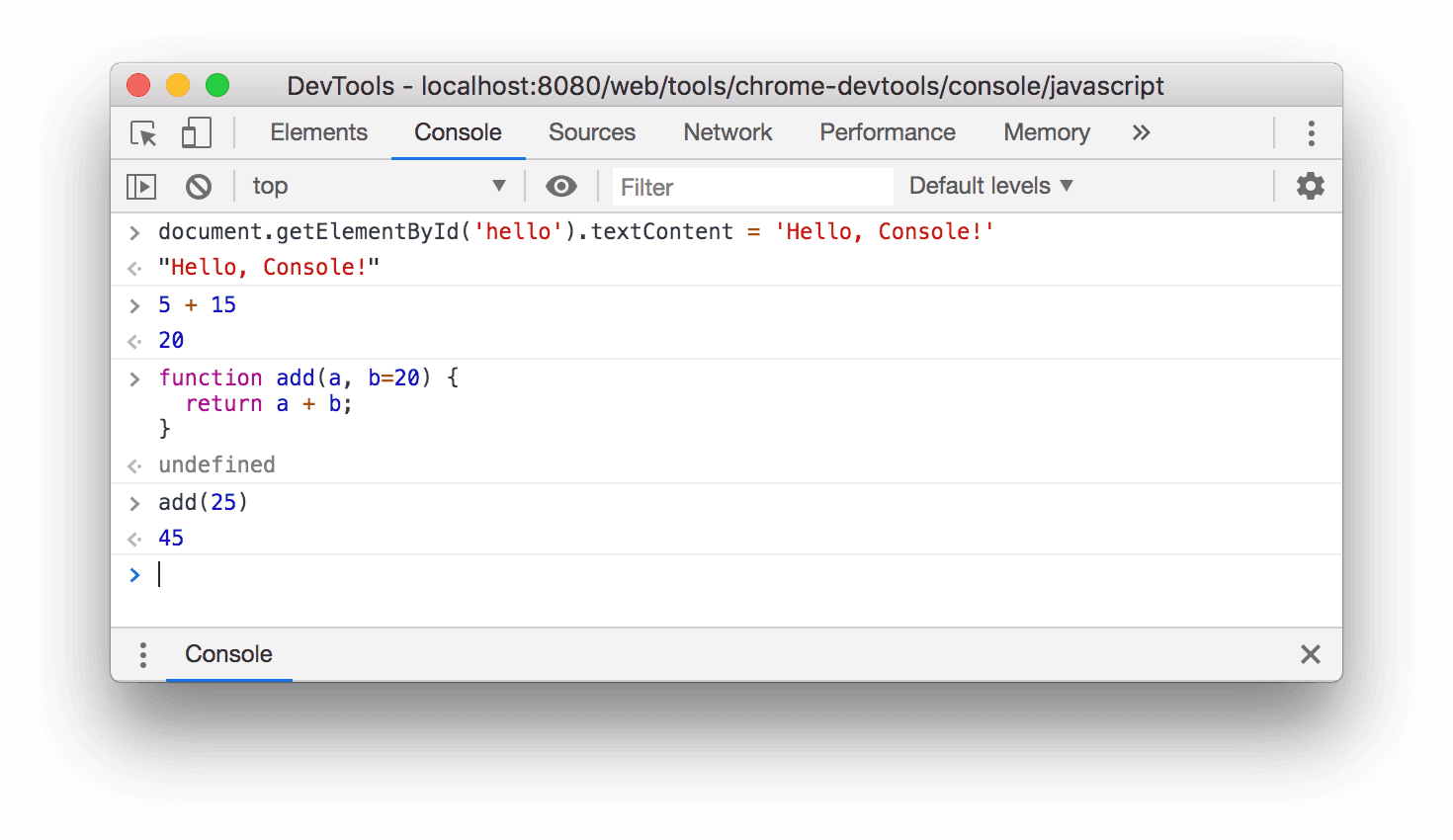

Open your browser’s developer tools again. (Perhaps on your published web page, or right here on this one). But this time, switch to the tab named Console.

This is an interactive JavaScript console, which means that you can type in JavaScript, hit enter, and it will calculate the result. Try adding two numbers by typing:

1 + 2

After hitting enter, a new line will be shown with the result: 3.

A piece of text, that a program works with, is called a string. In JavaScript, strings need to be wrapped either in single quotes ', double quotes ", or backticks `. Type:

'1' + "2 cats"

and hit enter. It returns "12 cats" (this time with quotes). That’s because when working on strings (as opposed to numbers), the + operator concatenates them together.

If you want your program to remember something for later, assign it to a variable. Create the variable myName and assign the string "Peter" to the variable:

const myName = "Peter";

You can see that it printed out undefined. That’s because the assignment statement itself doesn’t return anything (as opposed to expressions). The semicolon is optional, but customary to mark the end of a statement.

The const at the beginning means you are declaring a constant: you cannot assign to this variable again within this part of the program (or within the same console session). You can try writing the above statement again, and you’ll get the error:

redeclaration of const myName

The third way to write a string is to wrap it in backticks. This allows you to put variables (and other expressions) in it using ${ }:

`I am ${myName} and ${3 * 10} years old`

Functions

If you want to execute the same kind of computation multiple times, you need a function. One way to write a function that returns the string "Hello World", and assign that function to the variable hello is as follows. (This is a so-called Arrow function, but there is an older function syntax as well.)

const hello = () => "Hello World";

Since it’s an assignment, it prints undefined into the console. But now you can call the function:

hello()

which will return the string "Hello World".

To make it a bit more useful, we can write a new function that takes an argument, which you can name as you wish. Let’s call our argument name:

const helloName = (name) => `Hello ${name}`;

You can call it like:

helloName("Peter")

Objects

Finally, let’s give you a sneak peak on JavaScript objects (which hold key-value pairs):

const person = { firstName: "Arthur", lastName: "Dent", age: 42 };

`${person.firstName} ${person.lastName} is ${person.age} years old.`

Arrays

And a sneak peak of arrays, which act like lists:

const shoppingList = ["bread", "milk", "butter"];

const rememberFn = (item) => `Remember the ${item}!`;

shoppingList.map(rememberFn)

.map() calls the method map on the shoppingList. A method is a function attached to an object. All arrays come with a map method. When you call it, you need to give it a special kind of argument: a function. The last two lines could also have been written as a single line:

shoppingList.map((item) => `Remember the ${item}!`)

Feel free to toy around a bit more in the JavaScript console. You can always reload the page to reset everything, meaning you’ll lose all your variables. This will allow you to declare them again with const.

The power of programming

The good news is that with JavaScript – like with any general-purpose programming language – you can create arbitrarily complex programs. Since we’re all human and usually make mistakes, that’s also the bad news.

Either way, this crash course should be enough for you to read and write some basic JavaScript, and follow the rest of the guide.

Want to learn more JavaScript?

MDN also has good documentation on JavaScript. But especially if you’re new to programming in general, I can highly recommend the book Eloquent JavaScript, which is free to read online.